Learning from Yucca Mountain

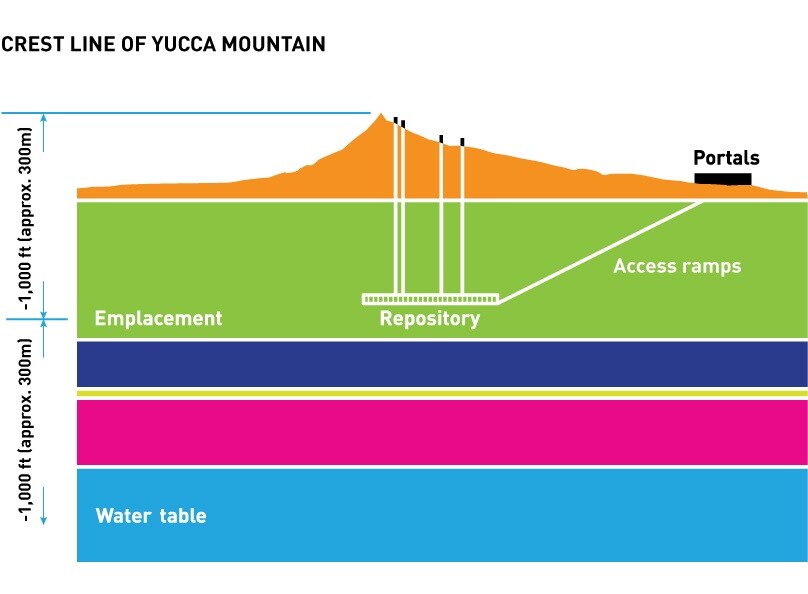

The US plan to bury used nuclear fuel deep in Yucca Mountain has been stalled for years, even though the site’s safety has been backed by science. Why?

The United States started with 50 possible sites. It quickly settled on Yucca Mountain, a former nuclear test site in Nevada. The US process lasted only a few years. It didn’t include public consultation, which gave rise to opposition.

There is a Canadian precedent too. In 1989, a commission studied the idea of placing a waste site in the granite of the Canadian Shield. In 1998, after public consultations, the Seaborn Commission said that the plan was technically sound: the waste could be stored safely there. But the commission also found that the idea hadn’t proven acceptable to the public. The Canadian government decided that public acceptability would be a requirement for any permanent storage plan.

Today in Canada, work is underway to find two sites for nuclear waste. One would store spent nuclear fuel. The other would store low- and intermediate-level waste.

Low-level nuclear waste includes mops, brooms, gloves and so on. It is not necessarily radioactive, but the nuclear industry takes a precautionary approach to protect people and the environment. Intermediate-level waste includes used reactor parts, and it is normally shielded from people and the environment.

Leaders of both Canadian projects are mindful of Yucca Mountain and the Seaborn Commission. The Nuclear Waste Management Organization has talked with 21 communities that said they might host a spent-fuel site. After screening for geological suitability, nine remain on the list.

For storing low- and intermediate-level waste, a site has already been selected, at Kincardine, Ontario. A federal government panel still has to approve the location. The panel found the site location and design to be safe – a finding backed by sound science. The panel also held extensive public consultations. As part of that work, the panel hired a group of experts to assess the public perception of risk about the project. According to Dr. William Leiss, who led that group, “This type of work exists in the shadow of Seaborn. It was quite clear that the Joint Review Panel was concerned about social acceptance.”

Kincardine’s mayor, Anne Eadie, agrees: “At the hearings, they really bent over backwards to hear everyone speak, and took any opportunity to hear all concerns.”

Back at the beginning of the consultation process, Kincardine asked its residents what they thought. In a 2005 phone survey, 60% of respondents agreed with the concept and 22% disagreed.

Ten years later, Mayor Eadie says, “The majority of residents still support the DGR. On the whole, they are much better informed, as most of them either work at the plant or have family members there.”

The report by Dr. Leiss’ group makes clear that public acceptance depends on a good understanding of risk. The consultations will continue as the project unfolds.