Nuclear Science: Unlocking Answers to Malnutrition

A healthy diet begins with having enough food to eat, but we need more than that. A healthy diet provides a balance of proteins, carbohydrates, fats, vitamins and minerals which are critical to growth, development and disease resistance.

A deficiency in minerals and vitamins is called hidden hunger. One might feel full but one’s growth and development can be stunted in the absence of necessary nutrients.

According to a 2014 report by the World Health Organization (WHO), hidden hunger and undernutrition affects nearly two billion people. That’s almost 1/3 of the global population.

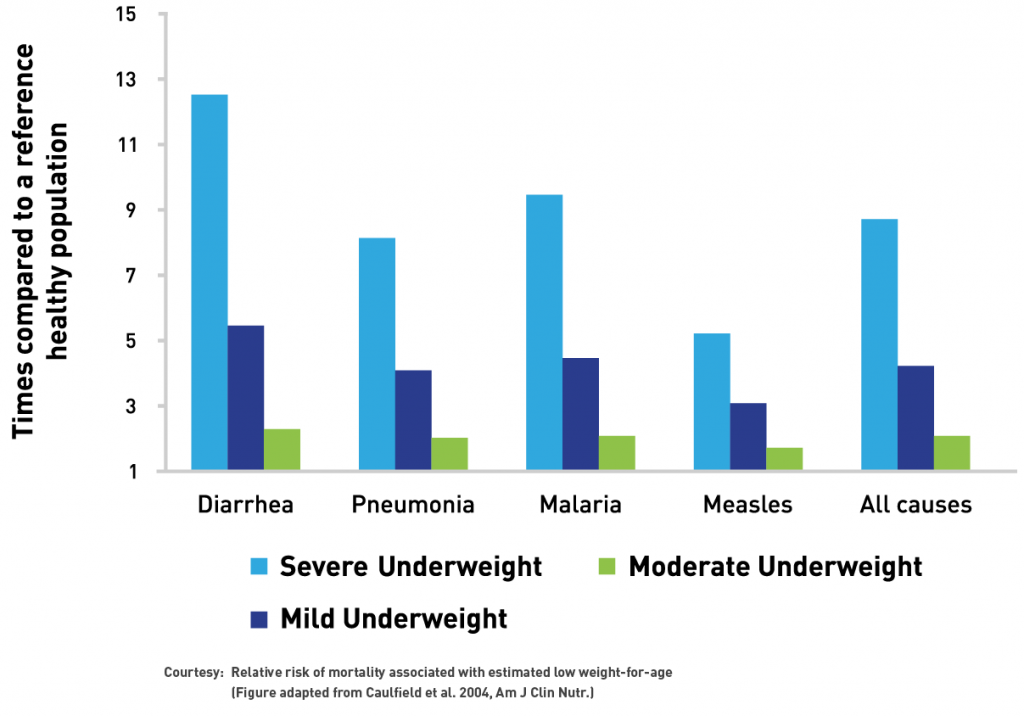

In 2013, 6.5 million children died before five years of age. And 45% of these deaths are linked to maternal and child malnutrition.

Increased child mortality is not the only impact of undernutrition. A lack of food variety coupled with unhealthy environments and limited access to health care can increase the risk of disease, and hold back mental and physical development.

“165 million children are stunted or not as tall as they should be for their age. In some cases, they are stunted not because they are hungry but because the quality of their diets is poor or because they are frequently sick.” Christine Slater, nutrition specialist at the IAEA.

Chronic infections and repeated illnesses in children, like respiratory infections, can be an indicator of a deficiency in essential nutrients.

Nuclear technology is one tool in the fight against malnutrition. A technique called deuterium dilution helps to determine body composition, or the percentage of fat versus fat-free mass.

Deuterium is a stable form of hydrogen that includes a neutron. It bonds with oxygen to make water that acts just like regular water, but weighs more because of the neutron.

Taken into the body through drinking, concentrated deuterium passes into the body’s water, and after a few hours is evenly distributed throughout the body water. Body water is sampled as saliva, urine or blood. From the amount of deuterium consumed, and the concentration in body water, we can calculate the amount of fat-free mass. If this is subtracted from body weight, we have an estimate of the amount of fat in the body.

Scientists think this measurement technique gives more reliable results—especially for children—than measuring skinfold thickness or body-mass index. It can be used to evaluate programs that provide children with nutrients to promote healthy growth while limiting the risk of obesity later in life.

Deuterium dilution techniques have been used for many years in high-income countries, according to Slater, and with the help if the IAEA Technical Cooperation Program, these benefits can be found in low- and middle-income countries as well.

There are many other applications. For example, cancer treatments often leave patients malnourished. This procedure could help provide doctors with better information on their patients’ nutritional status.

As Slater points out, malnutrition is a complex problem requiring a multi-pronged solution that includes a better diet and cleaner environment. An effective diagnosis helps makes the solution possible.

“Malnutrition is not just to do with food and quality of diet but environmental influences,” says Slater. “Children who live in dirty environments and don’t have access to good sanitation can get sick and we find in a lot of cases that their guts are damaged. So even if they get good quality food they can’t absorb the nutrients.”